As some of you know, I’m writing a book about the Kearny Cross: a medal which was awarded by Union General David B. Birney (and named in memory of his predecessor) to members of the First Division, Third Corps, Army of the Potomac.

There were two versions of the medal: the “Kearny Medal of Honor” for officers and the “Kearny Cross of Valor” for enlisted men. They’re often referred to collectively as the “Kearny Cross.” Although they were actively awarded over the course of at least two years (Dec ’62-Dec-’64), the only published list of recipients of the Kearny Cross was issued by Gen. Birney in the form of General Order #48 following the Battle of Chancellorsville in early May, 1863. That order identified 454 “meritorious and distinguished non-commissioned officers and privates, selected for their gallantry” and lists the recipients by name.

An unusual characteristic of this order is that it included two women – volunteer field nurses or “vivandiers” named Anna Etheridge and Mary Tepe who were noted for their bravery because they went onto the battlefield to tend to the wounded of both sides, even as bullets flew all around them.

But my research has uncovered at least two more women who received this medal. I thought that I would relate the story of my efforts to track one of these previously-unknown female recipients of the Kearny Cross.

I first encountered a reference to Charlotte E. McKay in a book that was published just two years after the end of the war called Woman’s Work in the Civil War: A Story of Heroism, Patriotism and Patience by L. P. Brockett, M.D., and Mary C. Vaughn. In it, the authors said about Charlotte:

“The officers and men who had been under her care in the Cavalry Corps Hospital, presented her on Christmas day, 1864, with an elegant gold badge and chain, with a suitable inscription, as a testimonial of their gratitude for her services” and “a magnificent Kearny Cross, with its motto and an inscription indicating by whom it was presented.”

I’m wary of any new source, however, and had not found any previous reference to Charlotte E. McKay as a recipient of the medal. I also know of several instances where a soldier claimed years later to have received a “Kearny Cross” but it turned out to be another kind of medal or even a souvenir badge or replica purchased from a sutler. So I decided to dig a little deeper into Charlotte’s story.

The book said that Mrs. McKay, “a resident of Massachusetts, had early in the war been bereaved of her husband and only child, not by the vicissitudes of the battle-field but by sickness at home.”

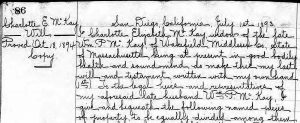

With the wonders of online search engines, it didn’t take long to find Charlotte’s tombstone in San Diego, California, giving her lifespan as 1818-1894. A few minutes later, I found Charlotte’s record in the 1860 Federal Census which showed her living alone with her then-5-year-old daughter, Julia L. McKay. With a little persistence, I was even able to find a copy of the last will and testament of “Charlotte Elizabeth McKay” among the Massachusetts State Probate Records. In it, she named her deceased husband as William P. McKay.

Most interestingly, she made a point in her will to bequeath to a nephew “my gold chain watch and my cavalry medal.” The Kearny Cross wasn’t a “cavalry medal” but you’ll recall that the book quoted above claimed that it and an “elegant gold badge and chain” were given to her by her patients at the Cavalry Corps Hospital – so it makes sense that Charlotte would refer to the medal as a “cavalry medal.” But it still wasn’t necessarily a Kearny Cross.

That initial source, the book Woman’s Work in the Civil War, related another interesting detail about Mrs. McKay. It said that “she witnessed the bloody but successful assault on Marye’s Heights, and while ministering to the wounded who covered all the ground in front of the fortified position, received the saddening intelligence that her brother, who was with Hooker at Chancellorsville, had been instantly killed in the protracted fighting there.”

I thought it was odd that the book didn’t name the brother or his regiment. If I could resolve those details, I thought, it would help to convince me that the source was also reliable when it identified Charlotte’s medal as a Kearny Cross.

Back to her last will and testament, I find that she referred to two living brothers – “J. S. Johnson” and “F. A. Johnson” – and two deceased ones – “T. S. Johnson” and “H. Johnson.” The soldier wasn’t necessarily one of the latter two (i.e., she may have had other dead brothers who were not mentioned in the will) but clearly, her maiden name was Johnson.

Continuing to dig, I found that the 1885 book History of the One Hundred and Forty-First Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1862-1865 by David Craft expressed that regiment’s appreciation for the nurses who tended their wounded. This book included just two sentences about “Mrs. Charlotte E. McKay.” There was no mention of her receiving a medal but the second sentence was this:

“Mrs. McKay had a brother in the Seventh Maine Regiment, who was killed at Chancellorsville, and she while the battle was still raging went fearlessly upon the field to care for him, and others who were wounded.”

Now I had a surname and a regiment! I happened to have the 1863 Adjutant General’s Report from the State of Maine on my bookshelf so I hurriedly flipped through the list of men in the 7th Maine Infantry looking for a soldier named “Johnson.” You can imagine my disappointment when I found that there were only two and they had both survived the war.

Shucks! If the story about the brother was wrong, then maybe my initial source’s description of her medal as a “Kearny Cross” couldn’t be trusted either.

I needed more supporting evidence – and a search of GoogleBooks produced it in the form of an even older book called Women of the War by Frank Moore. This book, published in 1866, said that Charlotte E. McKay “had received a magnificent Kearny Cross, with the front inscription, ‘Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori;’ and on the reverse, “Presented to Mrs. C. E. McKay, by the officers of the Seventeenth regiment Maine volunteers, May, 1863.”

The Latin inscription translates to “It is sweet and glorious to die for one’s country” which is the correct inscription for an authentic Kearny Medal (the officers’ version)!

The book goes on: “Early in January, 1863, she was, after much difficulty, furnished with a pass which admitted her within the army lines at Falmouth, where the army was encamped. She spent several days in visiting her brother and other friends in the Seventeenth Maine volunteers” So her brother was in the 17th (not 7th!) Maine Infantry.

And then the authors related this little anecdote which happened after the brother’s death:

”We have lost too much to give up now; we have something to revenge,” said Captain F., her brother’s friend and tent-mate, as he stood one evening in front of her tent, just ready to mount his horse and ride away. He was very pale, and there was a gravity in his manner quite unnatural, for he was usually gay, and apparently light-hearted. A few weeks later, and he lay writhing in pain, and dying on the bloody field of Gettysburg.”

It is worth noting that an enlisted man would not likely be bunked in the same tent as a “Captain F.” Charlotte’s brother was almost certainly an officer.

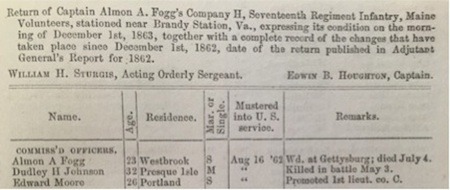

So, I thought, now I have to find an officer named Johnson in the 17th Maine Infantry who was killed at Chancellorsville and was in the same company with a Captain whose last name started with F. and died at Gettysburg. Back to the Adjutant General’s report…

And there it was:

“Oh, Dudley,” I cried out, “I’ve been looking for you, buddy!” The tent-mate was Captain Almon A. Fogg and their fates described in the right-hand column were a perfect match.

But as exciting as that was, the connection between Charlotte and this Dudley H. Johnson was still just a theory. I needed to prove a direct connection between them. But then I noticed that Dudley’s marital status is given as “M.” While Dudley didn’t survive to collect a pension, maybe his wife did!

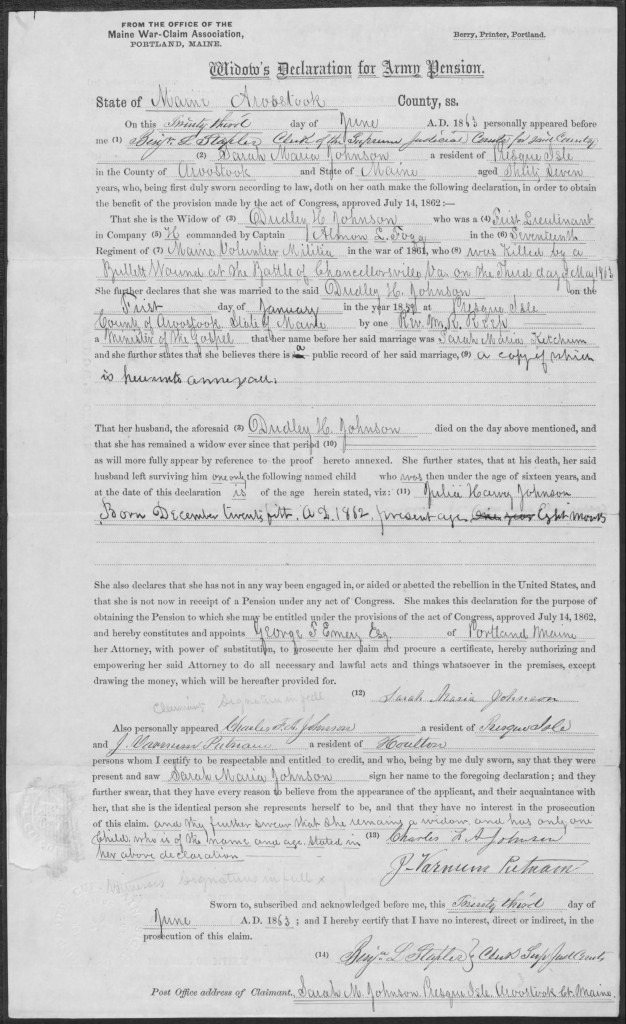

Oh so conveniently, Fold3.com includes full digital copies of Civil War widows’ pension files online. And sure enough, on 23 June 1863, a Sarah Marie Johnson filed for an army pension citing the service of her deceased husband, First Lieutenant Dudley H. Johnson, Company H, 17th Maine Infantry who “was killed by a bullet wound at the Battle of Chancellorsville on the third day of May, 1863.” The pension was granted with minimal paperwork.

Ten years later, however, Sarah applied for an increase to the pension amount. In the interim, she had moved to New Brunswick, Canada – a decision which greatly complicated the matter. Suspicious government investigators insisted that, unless she could prove that the dead soldier had been a U.S. citizen, Sarah might lose her pension altogether. What followed was a flurry of correspondence and affidavits as Sarah tried desperately to justify her pension. I’m sure that it was a time of great stress for poor Sarah – but it was a blessing for me.

Her pension file became thick with documentation and on the very last page (of course!) was a witness’ affidavit in support of Sarah. The witness’ testimony began:

“Dudley H. Johnson was my youngest brother. Said Dudley was a citizen of the United States. I was twelve years old at the time of birth of my brother, Dudley H. Johnson, and I have a distinct recollection of the same in Sullivan, Hancock County, State of Maine.”

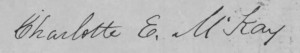

At the bottom of the page was the witness’ signature:

And so the circle of evidence is complete and I think that Charlotte can join the very short list of women who received a medal for bravery during the U.S. Civil War.

Now if only I could find a photograph of her!

The only official published list includes 454 recipients of the Kearny Cross. But so far, my research has identified 804 recipients, culled from hundreds of sources, including regimental histories, diaries, newspaper accounts, unpublished manuscripts, and obituaries, among others. In addition to a comprehensive list, I hope in my book to present a short biography in tribute to each recipient.

1 down, 803 to go.