The American Civil War was fought from 1861 to 1865 and the average soldier was 18-45 years old. So if you have a white, male ancestor who was born between roughly 1816 and 1847 and lived in the United States in the early 1860s, then he probably played some part in the Civil War.

This is a general rule but there were many exceptions of drummer boys as young as 12, as well as men 60 years old or more who enlisted. In addition, more than 175,000 free black men, more than 3,000 native Americans, and at least 400 women (disguised as men) also served in the war. Then there were civilian scouts, teamsters, doctors, nurses, and other support personnel who weren’t technically soldiers but who worked under contract with the army. Lastly, the Southern armies were accompanied by thousands of “body servants” and “laborers” (i.e., slaves).

But how would you determine whether your ancestor fell into one of these categories?

Or perhaps you know that your ancestor served in the war but you hope to find out some details of his service?

Following are some of the more popular and productive sources for records of Civil War service:

Index:

- Family Records

- Soldiers and Sailors Database

- 1890 Federal Census Fragment

- 1890 Veterans Schedule

- 1910 Federal Census

- 1930 Federal Census

- Service Records

- Pension Records

- “The Official Records”

- State Archives and Genealogical/Historical Societies

- Newspapers

- Burial Databases

- Other Burial Records

- Online Family Trees

- Web searches

- Books

- Other Sources

- Hire a Genealogist

Family Records

Most people get their first exposure to their ancestry from material that is passed down through their family. With luck, you might have family tree charts, copies of important documents, a family Bible, medals and other memorabilia, and maybe even a photograph or two. These types of materials are your best source for clues to the possible Civil War service of your ancestor(s).

Many families have a self-appointed “family historian” who maintains these records and perhaps even actively researches their ancestry. But you may be surprised to know that many people have no interest whatsoever in such things. All it may take is a question and you’ll discover that Aunt Martha has “a box of old stuff” in the attic. In other words, start with your family.

Remember that many Civil War soldiers enlisted and went off to war with their fathers, sons, and brothers. So your ancestors’ records may be in the possession of your great-great-granduncle’s descendants. That is, your cousins.

It is common for such things to be passed down through female lines. So don’t focus exclusively on the family lines that still bear your surname. Ask the living descendants in every branch of your family. You never know what you might find and you might save what would otherwise take years of research.

Soldiers and Sailors Database

Your first challenge may be to determine the regiment in which your ancestor served. For that, experienced researchers have relied for many years on the “Soldiers and Sailors” database which was offered by the National Park Service. However, the NPS announced in 2025 that it will no longer maintain or support that system.

Fortunately, there is a free alternative called “Better Soldiers and Sailors” which uses the same database as the old system. It is not only actively maintained but it offers advanced search features that were not offered by the NPS’ system.

It is worth noting that many soldiers served in a regiment that was not formed in the state of their residence at the time of enlistment. The many reasons for this are beyond the scope of this article, but don’t limit your search to one state if you can avoid doing so. If it becomes necessary to do so (because the list of candidates is otherwise just too overwhelming), then start by searching any state in which he lived before, during, or after the war, as well as those where he, his wife, and children were known to have been born, died, and/or were buried.

Conversely, don’t assume that you have found your ancestor just because it is the only matching name in the database. With more than 2.5 million soldiers who served, there’s a good chance that more than one soldier had your ancestor’s name – and the others may be missing, misspelled, or abbreviated in the database.

Best of all, if your soldier’s records are online, “Better Soldiers and Sailors” will tell you where to find them. If they aren’t online, then the system offers an easy and inexpensive way to order copies to be sent to you by GopherRecords.com.

1890 Federal Census Fragment

While you may have heard that the 1890 Federal Census was destroyed by a fire at the Commerce Department in 1921, you may not know that 1233 of those pages actually survived.

In particular, the pages (or fragments thereof) still exist for a few counties in Alabama, Georgia, Illinois, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, South Dakota, and Texas, as well as for a few streets in Washington D.C. They can be found on Ancestry ($) and FamilySearch (free).

The surviving records represent only 6,160 of the 62,979,766 people who were enumerated – but it could be a real treasure if your ancestor happens to be one of them!

Pro tip: The specific geographic areas with surviving records from the 1890 Federal Census are itemized at the bottom of this page. Note, however, that the location reflects the residence of each person in 1890, not the state of his military service, if any.

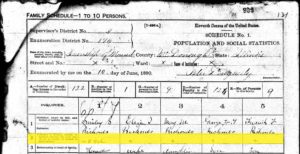

Row #2 of that census asked whether each person was “a soldier, sailor, or marine during the civil war (U.S. or Conf.), or widow of such person.” The enumerators were instructed to record ‘‘Sol’’ for soldier, ‘‘Sail’’ for sailor, and ‘‘Ma’’ for marine followed by “U.S.” for Union or “Conf.” for Confederate. The whole value was preceded by “W.” in the case of a widow of a veteran, e.g., “W. Sol (U.S.)”. As with the example shown here, however, those instructions were not always followed precisely.

1890 Veterans Schedule

Although most of the 1890 Federal Census was destroyed, a special enumeration of veterans had been conducted at the same time in order to help the U.S. Pension Office measure the population of veterans and their widows who were eligible for pensions. The intent was to identify Union Veterans of the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps of the Civil War, but some Confederate veterans were included, as were some veterans of other wars.

Sadly, much of the 1890 Veterans Schedule was also lost before it came into custody of the National Archives in 1943. Specifically, most of the records are missing from the states of Alabama through Kansas (alphabetically), as are about half of the records from Kentucky. The veterans schedule of the other 34 states and territories (Louisiana through Wyoming, plus Washington D.C.) were preserved, however. The surviving records can be found on Ancestry ($), MyHeritage ($), FindMyPast ($), and FamilySearch (free).

Pro tip: A veteran’s record will be found in his state of residence in 1890, not according to the state for which he served in the war. Also, the 1890 Veterans Schedule may be useful even if the soldier died before that year because his widow may be listed along with details of the soldier’s service.

Although the 1890 Veterans Schedule is often overlooked when service records are found elsewhere, it contains remarkable detail that is sometimes not found anywhere else, including an alias used by the veteran, the nature of his wound or cause of death, and/or his street address as of 1890.

Note that the numbered line with the widow/veteran’s name corresponds to the line with the same number on the bottom half of the page, which contains more information.

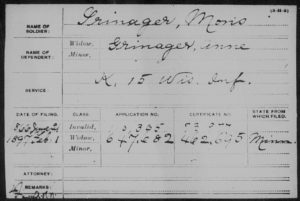

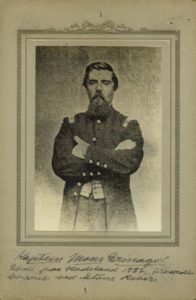

This example from Minneapolis, Minnesota, for instance, shows Anne, the widow of Captain Mons Grinager, who served in Co. K, 15th Wisconsin Infantry. It shows the dates of his service, the fact that he received a gunshot wound through the calf of his leg, and that Anne lived at 510 15th Avenue, S.E. (Minneapolis) in 1890!

1910 Federal Census

If your ancestor survived until at least April of 1910, his Civil War service may be noted in Column 30 of the 1910 Federal Census. Those records can be found on Ancestry ($), MyHeritage ($), and FamilySearch (free).

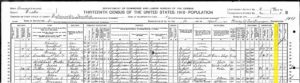

Enumerators were asked to record in that column if each person was a “Survivor of the Union or Confederate Army or Navy.” The values that you might find there are “UA” for Union Army, “UN” for Union Navy, “CA” for Confederate Army, and “CN” for Confederate Navy.

As in the example shown here, you will often find numbers in Column 30-32 but they are not relevant to the question of Civil War service. After the census, tabulators for the Census Bureau used those same columns to record some unrelated statistical data. So don’t be misled by the presence of numbers in that column.

While the presence of a “UA” (or “ua”), for instance, in Column 30 is usually a good indicator that the person was a veteran of the Civil War, the absence of such a record does NOT mean that he did not serve. As with almost every type of record, mistakes were made. And some veterans (especially former Confederate soldiers living in the north) may have been reluctant to acknowledge their wartime experience.

Pro tip: The evidence suggests that some enumerators were much more diligent in recording that column than were others. Look throughout the rest of the page and adjacent pages that were recorded by the same enumerator (whose name is listed at the top). If the enumerator never encountered a Civil War veteran, then you may have more reason to doubt that the record is accurate with respect to your ancestor.

1930 Federal Census

Similarly, if your ancestor lived until at least April of 1930, then his service may be noted in the 1930 Federal Census. Those records can be found on Ancestry ($), MyHeritage ($), and FamilySearch (free).

Column 30 in the census asks whether each person was “a veteran of U.S. military or naval forces.” If yes, then Column 31 may indicate “CW” for Civil War.

Other possible values in Column 31 include “WW” (World War), “Sp” (Spanish-American War), “Phil” (Philippine Insurrection), “Box” (Boxer Rebellion), and “Mex” (Mexican War).

Pro tip: As noted previously, the 1890 and 1910 Censuses explicitly distinguished Union and Confederate veterans. While the column headings in the 1930 Census ask about the “U.S. military or naval forces,” there is (and was) disagreement about whether those columns were intended to include Confederate veterans. So, as before, a “Yes” and “CW” is strong evidence that your ancestor served in the Civil War but a “No” (or blank) in Column 30 should not be taken as definitive evidence that he did not serve.

Service Records

The National Archives and Records Administration (aka “NARA”) in Washington D.C. holds the extant service records for the Union and Confederate armies and navies.

Starting in 1903, the Records and Pension Office recorded abstracts of all of the personnel records for volunteer regiments that it could find, including muster rolls, rosters, hospital rolls, and Union prison records and constructed what are called “Compiled Military Service Records” (aka “CMSRs”).

The contents of a CMSR is mostly military in nature but may include a few details to help establish that he is your ancestor.

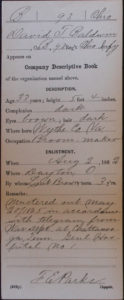

The file often includes the date and place at which he was mustered in and out and the period for which he enlisted. For Union soldiers, the CMSR sometimes contains a card indicating the soldier’s age at enlistment, his birth place, occupation before the war, and some physical characteristics, including height, complexion, and eye/hair color.

Then the CMSR typically contains a series of cards, each representing a bi-monthly payroll period, and indicating whether or not the soldier was present (or on detached service, sick in a hospital, AWOL, etc.) during that period. It also may include some details if the soldier was wounded or held as a prisoner of war. In rare cases it contains some copies of original or supporting documents like enlistment papers, requests for furlough, etc.

Many Union and Confederate service records are digitized and online, as are some enlistment and draft records. Those records that are not online can be obtained from the National Archives. In some cases, you’ll first need to find the soldier in one of the many service file indexes.

For a more complete description of the contents of service files and where/how to find them, please see this page.

Pension Records

Surviving veterans or their widows/dependents were eligible for a pension under some circumstances and those files can be a treasure trove of genealogical information.

Pro Tip: Pension files even exist for many soldiers who didn’t receive a pension! Of course, this includes soldiers who died during the war if a spouse or dependent subsequently claimed a pension based on his service. But there are also many thousands of pension applications which were explicitly denied – either because the soldier died before the application process was complete, failed to provide the necessary documentation, or was proved to be a fraud, deserter, or convicted by Court Martial. Most of those applications and supporting documents still exist.

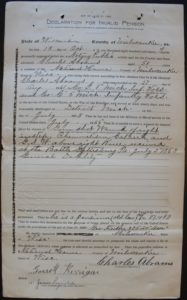

To qualify for a pension, the veteran would have to demonstrate that he met the requirements that were specified in the law. Those laws changed over time but it typically meant that the veteran had to detail his honorable service (later confirmed through records of the Adjutant General’s office) and to provide evidence of his disability, if any.

In the case where the application was made by a widow or dependent, they would further have to prove their relationship to the soldier, the fact that he had died, and sometimes the degree of their financial hardship. This additional burden of proof means that pension files very often contain copies of original documents like marriage certificates, death certificates, affidavits by relatives and witnesses, testimonials of fellow soldiers, the names and birth dates of dependent children, and much more.

Only a small percentage of Union pension files have been digitized and can be obtained online. In most cases, you’ll need to obtain copies from the National Archives.

The first step is to find the soldier in one or more of the online pension indexes. In fact, the online index cards themselves often contain a wealth of genealogical data.

Confederate pensions were awarded and managed by the individual Southern states. The pension qualifications varied by state as does the current method to access the surviving records – but many of those are also online.

For more details about pension files and where/how to obtain copies of them, please see this page.

“The Official Records”

During the war each officer was required to submit regular reports to his superior officer detailing the activity of his unit. A massive collection of those reports (both Union and Confederate), as well as official correspondence between officers was published in a 128-volume set called “The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies” (aka “the Official Records” or just “the O.R.s”). A comparable set is comprised of the “Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies” which is also searchable on Fold3.com ($).

If your ancestor was an officer in the Union or Confederate army or navy, then he is very likely mentioned in the O.R.s. But many enlisted men are mentioned as well. Officers’ after-battle reports often conclude with a list of killed or seriously wounded, as well as those who demonstrated particular bravery during a battle.

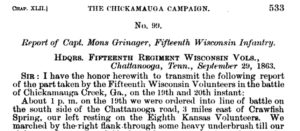

Pro tip: Follow one of the links above. If your search term (e.g., Mons Grinager) gets too many hits, then enclose it in quotation marks (e.g., “Mons Grinager”) or use the Advanced Search tool. If you know the soldier’s middle name or initial, then search with different combinations.

A “Supplement to the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies” by Janet B. Hewett, et al., was published by Broadfoot Publishing Co. of Wilmington, NC in 1994-1997. It is comprised of 100 more volumes of documents and diaries that were not included in the original O.R.s. Many of these supplemental volumes and their indexes are searchable online but the full text is available only in print at this writing (2020). Check WorldCat for a library in your area that has a copy of this collection.

You can also purchase a huge PDF containing the Official Records from CivilWarDigital.com for just $24.95 and it includes five other digital collections of your choice (e.g., Official Records of the Navy, Confederate Veteran Magazine, Southern Historical Society Papers, Battles & Leaders, etc.)

State Archives and Genealogical/Historical Societies

Many state archives and local societies have professional websites that contain their searchable catalog and, in some cases, a huge searchable collection of digitized original records.

Most such archives and societies are also quick to tell you that they have a long list of resources that are not available online, including local biographies, maps, property records, cemetery records, rare books, unpublished manuscripts, physical artifacts, photographs, and much more. They also have experienced researchers who are very familiar with those resources.

Be sure to check the State Archives and state/county/city societies in the area where your ancestor lived before and after the war, as well as where he was born, died, or is buried if they are different. If you don’t know where those locations are, start with the societies for areas that you know are associated with his parents, siblings, spouse, and/or children.

If a visit is not practical, you’ll often find a helpful researcher with a phone call or email to those societies. Be prepared to provide all of the details that you know about the soldier and his relatives. Be aware that the society may have very limited hours and limited volunteer staff, so be prepared to wait for an answer. Also, photocopying fees might apply.

In some cases, you may want to hire a professional genealogist (see below) who is local to your area of interest and is familiar with these records.

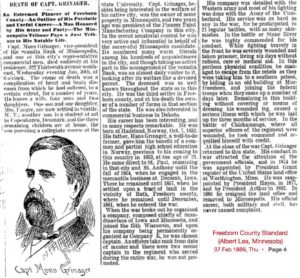

Newspapers

Contemporary newspapers accounts may list draftees, those killed or wounded in a particular battle, exploits of hometown heroes, or obituaries which cite your soldier’s service. Newspaper accounts of funerals may also include a list of fellow soldiers in attendance which may be a clue to the service record of the deceased.

Digitized historical newspapers can be found on:

- Newspapers.com ($)

- NewspaperArchive.com ($)

- GenealogyBank.com ($)

- MyHeritage.com ($)

- Google News (free)

- ChroniclingAmerica.loc.gov (free)

- ProQuest ($)

- …and a wide variety of state and local sites.

Each collection contains a specific set of newspapers and covers a limited time frame, however, and each site is different. So check that the collection contains newspapers for the time and place that is applicable for your ancestor.

Burial Databases

Many burial sites and tombstones have been recorded on FindAGrave.com and BillionGraves.com. These free and searchable sites often include photographs or transcriptions of the tombstone, genealogical information about the deceased, and even a photograph of the soldier. In many cases, the biographical information and sometimes the tombstones themselves include specific references or symbology suggesting the military service of the deceased.

Be aware, however, that – unlike most of the other sources in this post – the data on these sites are submitted by other researchers and are not official or contemporary records. They frequently include false information, errors of transcription, and erroneous family connections. So, while they can contain excellent clues for further research, the information on these sites should always be taken with a grain of salt.

There are distinct benefits to such sites too, however, and one of them is often overlooked. The people who contributed the data and photographs, are researchers themselves and may be your relatives! While some such contributors may be engaged in documenting whole cemeteries, for instance, many of them may share a common research interest with you. So click on their name and send them a note! A polite and respectful (i.e., not demanding) inquiry may very well lead you to a kindred spirit who is happy to help you – especially if you offer to share what you know in exchange.

The same is true for people who comment or leave digital “flowers” on those records. Many of them are relatives of the subject person – and therefore your relatives. While you’re at it, comment or leave “flowers” yourself. Another researcher might find you!

Lastly, if there are links to relatives of the subject person (e.g., parents, spouses or children), then follow those links. Then contact the researchers associated with those records. They might be more-distant relatives but they might know that crucial piece of information that you are missing.

Other Burial Records

If your ancestor was buried in a National Cemetery, military post, or other veteran burial site, or in a private cemetery where the grave is marked with a government headstone, then you should check:

- The National Gravesite Locator (free)

- U.S. Veteran Cemeteries on Internment.net (free)

- U.S. Veterans’ Gravesites on Ancestry ($) and Fold3 ($)

- United States Records of Headstones of Deceased Union Veterans, 1879-1903 (FS)

- Military Headstones in National Cemeteries on Ancestry ($)

- U.S. Burial Registers by the NCA on Ancestry ($).

- U.S. Military Burial Registers by the Quartermaster General on Ancestry ($).

- U.S., Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963 on Ancestry ($).

Other grave registries include:

- The National Graves Registration Database by the SUVCW (free)

- Sons of Confederate Veterans Confederate Graves Registry by the SCV (free)

Databases for specific large cemeteries with Civil War burials include:

- Arlington National Cemetery (free)

- Hollywood Cemetery (Richmond, VA) on Ancestry.com ($)

- Congressional Cemetery (Washington, D.C.) (free)

Finally, Ancestry.com ($) has compilations of records for Civil War veterans who are buried in New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, or Iowa.

For burials in other states, check Cyndislist.com (free) and the websites for a specific State Archives, historical society, or genealogical society.

Online Family Trees

Like the burial databases listed above, online family trees (including those on Ancestry.com ($) and MyHeritage ($)) are created by other researchers who – let’s just say – apply a wide range of research standards. So while those trees can be good sources of clues, they too are fraught with errors.

The most useful and reliable online trees are those which cite their sources. In many cases, you’ll find family trees that include direct links to relevant census records, military records, books, and more. So, rather than just accept the conclusions of those researchers, look at their sources and judge their value for yourself.

Online family trees which cite only other online family trees are all but useless.

Don’t even assume that a linked source is necessarily appropriate for the person who is the subject of that page. Some researchers will accept and cite a source based solely on the fact that the name is correct. Examine every source with a skeptical eye.

And like the burial sites mentioned above, one of the best things about online family trees is that they identify researchers who are interested in the same people that you are! So click on their name and send a friendly note offering to exchange information.

This is true even for “private” family trees. Such researchers are often happy to share information with you but they make their trees private so that you have to contact them and identify yourself in order to get details. As a condition of sharing data, they may insist that you cite them in your own research. This is their way of thwarting the disreputable researchers who would otherwise not give them credit for their hard work.

Web Searches

Sometimes, the simplest and most productive research method is the easiest to overlook. Don’t neglect to do a simple web search for your ancestor’s name. You may discover a reference to his name in a regimental roster, association membership, or an online discussion list, among many other possibilities.

Pro tip: Take the time to learn the advanced search methods for your favorite search engine. Even searches for common names can be winnowed down to a manageable list using powerful search operators.

With Google, for instance, did you know that you can restrict your search to pages that reference a certain year range?

“Franklin H. Johnston” 1840..1842

You can also search for alternative spellings:

(Philip OR Phillip) (Kearny OR Kearney)

And you can exclude pages that reference specific words:

“Thomas J. Hanks” -actor

You can even search with a wildcard (asterisk) to represent an unknown middle name, initial, or other intervening text:

“Leander * Buttermore”

Note that this last example requires that there be some intervening text so it produces very different results than a search for “Leander Buttermore”.

Pro tip: Unless your ancestor’s first and last names are very unusual, your search term should typically be in quotes in order to avoid thousands of false positives. But make a point of searching with first-name-first (e.g., “George B. Chalmers”) and last-name-first (e.g., “Chalmers, George B.”) since some alphabetical lists use the latter format and would otherwise be missed. Lastly, as with other resources listed in this article, search for as many spelling variations (e.g., McDonald and MacDonald) and permutations of the same name (e.g., with and without middle names/initials) as you can imagine.

If you can’t remember the syntax for these different search terms, Google even has a fill-in-the-blank version of the search form.

Best of all, you can combine these advanced search operators and strategies to produce very targeted search results!

Books

Regimental histories, regional genealogies, or other published biographies are often available online but may not show up (or may be lost in a tidal wave of other search results) using a standard web search. They might include a reference to your soldier.

Google Books, Internet Archive, FamilySearch Digital Library, and the Gutenberg Project, for instance, offer free full-text searches of millions of online books. There are many other sites (both free and subscription) that do the same – and some of those specialize in specific geographical regions.

As described above for other kinds of web searches, be sure to search for your soldier’s name within quotes, without quotes, with and without a middle name/initial, by first-name-first, and by last-name-first.

Rare or out-of-print books are often available for purchase from online used-book stores like AbeBooks.com, Biblio,com, or even Amazon.com (which, after all, started its life as a book store). Many more modern books also give detailed histories and an indexed roster of a specific regiment or battle.

If you suspect that your ancestor is referenced in a book but you can’t find it online, then find it in a library using WorldCat.org.

Other Sources

A detailed catalog and description of military records that are housed at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) can be found in this document.

Searching the main pages on major sites like The National Archives (free), Fold3 ($), Ancestry ($), FamilySearch (free), and MyHeritage ($) can frequently result in many thousands of “hits,” making it hard to find the records for your specific soldier. So if you know what kind of record you want, it is usually most effective to search that database directly by following a link like those in this article. But if you enter all of the information that you know about the soldier, including birth date/place, spouse name, etc.), then you might find your way through the weeds and discover record types that you didn’t know existed!

The American Civil War Research Database ($) includes a database of soldiers, a photo directory, and more. It may be well worth the small investment for a membership.

The Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (the successor to the Grand Army of the Republic or “G.A.R.”) and the Sons of Confederate Veterans have online databases, grave registries, educational programs, and volunteer researchers who would be able to help you navigate the records of those organizations. They also have local chapters with social media pages. While memberships are encouraged, they are not required in order to access many of their resources.

Online discussion forums like CivilWarTalk.com, Military History Online, The American Civil War Forum, The American Civil War discussion group, Armchair General, and Jgg’s Civil War Talk, among others, are frequented by experts on a variety of topics (and even more amateur researchers) who may be able to help guide your research.

Finally, Cyndislist.com is a categorized and cross-referenced index to genealogical sources on the internet and is a tremendous resource for all researchers. The Civil War sub-category on Cyndislist.com contains thousands of helpful links to military records of all types.

Hire a Genealogist

This list represents the most common sources for Civil War records but it is far from comprehensive.

If you’ve hit a brick wall and/or you need help to find your ancestor’s records, you should consider hiring a professional genealogist. They are expert researchers who are well-versed in using these types of records and many more.

Many professional genealogists specialize in Civil War research in a specific state – so you may want to find one that is local to your area of interest. They will be able to access the many types of records that are stored in local court houses, historical societies, etc., and are available ONLY in person.

To find a professional researcher, visit Board for Certification of Genealogists, LegacyTree.com, and/or ProGenealogists.com.

Please post comments or questions about this post below.

Copyright © 2020, Gopher Records, LLC