Available for:

- War of 1812

- Mexican-American

- Early Indian Wars

- Civil War

- Spanish-American War

Compiled Military Service Records (CMSR) is a collection of each soldier’s military records that were gathered together from a variety of original sources, including muster rolls, hospital records, casualty sheets, etc. The CMSRs are therefore derivative records, compiled in the late 1800s and early 1900s to quickly verify service and facilitate pension processing.

The outer jacket indicates the soldier’s name (and sometimes aliases), company, regiment, ranks upon mustering in/out, a list of abstract cards, the number of personal papers, and sometimes a bookmark and/or cross-reference.

They typically contain card abstracts representing by-monthly pay periods and indicating for each period whether the soldier was present, absent, missing, on detached service, on furlough, in a hospital, held as a prisoner of war, deserted, killed, etc. They also commonly indicate when and where the soldier mustered in and out and his rank at those times. A soldier’s service record will frequently mention when he was a promoted, transferred, resigned, or discharged, for instance.

In some cases, a service record will include “personal papers” or supporting documentation like enlistment papers, copies of orders, casualty reports, hospital records, prisoner of war records, a discharge certificate, record of death and internment, inventory of personal effects (upon death), correspondence, and others.

Although the information in service records are recorded for military purposes, they sometimes contain some biographical or genealogical details, including aliases and spelling variations, age or year of birth, place of birth or residence, a physical description, occupation before the war, and, in more rare cases, even the name/address of a spouse or parent.

Pro Tip: A soldier’s service file, pension file, and carded medical records can all be very enlightening. They served different purposes and therefore focus on different kinds of data. For the most complete picture of the soldier’s life, military service, physical condition, and family, you should obtain copies of all of those files whenever possible. (See the description of the Civil War Soldier’s Bundle below.)

Normally, there is an independent fee for each service record that we retrieve but you may save some money with our Civil War Soldier’s Bundle. The bundle includes the soldier’s service records, pension file, and carded medical records at a discounted bundle price. Moreover, if the soldier served in more than one regiment, then the bundle includes ALL of his service records and carded medical records which can be much less expensive than ordering them separately.

Normally, there is an independent fee for each service record that we retrieve but you may save some money with our Civil War Soldier’s Bundle. The bundle includes the soldier’s service records, pension file, and carded medical records at a discounted bundle price. Moreover, if the soldier served in more than one regiment, then the bundle includes ALL of his service records and carded medical records which can be much less expensive than ordering them separately.Note that soldiers very commonly served in more than one unit. Upon being discharged with a disability, a soldier might also have re-enlisted for light duty in the “Veteran Reserve Corps.” There should be an independent service file for each unit in which he served.

Sometimes the bottom of a service file jacket will reflect a “book mark.” That is typically a reference to an investigation by the Adjutant General’s Office in order to resolve an error or ambiguity that was discovered in the original records. The book mark case file (if it still exists) will be retrieved and digitized as part of the service file at no additional charge.

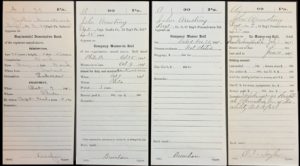

Following are a few sample cards from a typical Civil War service record. (Click to zoom in).

Of course, the file may contain many more cards, as well as other documents as described above. The size of the file is typically a function of the soldier’s term of service. That is, soldiers who were in the unit for longer time will usually have larger service files. Your soldier’s service file may contain a different number and combination of cards, of course. Every service file is different.

Of course, the file may contain many more cards, as well as other documents as described above. The size of the file is typically a function of the soldier’s term of service. That is, soldiers who were in the unit for longer time will usually have larger service files. Your soldier’s service file may contain a different number and combination of cards, of course. Every service file is different.

Full service files for Union soldiers in the Civil War are online on Fold3.com ($) for:

- the Union states of California, Massachusetts, Oregon, Vermont, and West Virginia.

- the Union regiments in the border states of Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri.

- the Union regiments that were formed in the Confederate states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia.

- the District of Columbia and western territories of Colorado, Dakota, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, and Utah.

Some special collections of Union service records have also been digitized by Fold3.com ($)

- United States Colored Troops

- 1st New York Volunteer Engineers

- Abstracts of Naval Officers Service Records

At Gopher Records, we have access to some powerful search tools that are not available to the general public – like the ability to search the Soldiers and Sailors Database for phonetic matches (Soundex or Metaphone).

Service files for any other state or regiment must be retrieved directly from the National Archives. In order for us to retrieve such a service file, it must first be located in an index. The Soldiers & Sailors Database (free) is maintained by the National Park Service and has transcriptions of the service record index cards. The actual index cards are searchable on Fold3 ($) and MyHeritage ($). Abstracts are also available on Ancestry (free) but to see the actual card, you’ll need to go to Fold3.

If you have a Service File Index Card, then please upload it when you place an order. If not, we will use all of our available tools in an effort to find it for you.

Confederate service files (to the extent that they still exist) have been digitized in their entirety and are online on Fold3.com ($).

Service files for the War of 1812, Mexican-American War, Early Indian Wars, Spanish-American War, and Philippine Insurrection are available only from the National Archives. Click on the appropriate link to order those records.

Our prices are based on a flat rate and do not vary based on the number of pages in the file(s). So while you will not be charged less if the file contains only a few pages, you will also not be charged more if the file is much larger than average.

Related links :

4 Comments

Barbara Sultan

Gopher Records

Sandra Chapman

Gopher Records