Principal Pension Indexes: To find a Civil War pension, you must first find it in an index. There are several types of indexes available online and they contain different – and sometimes conflicting – kinds of data. It is therefore critical that you understand the differences and consult the correct index(es), depending on your purpose.

Table of Contents

- PART 1: Introduction

- PART 2: Terminology & Abbreviations

- PART 3: Eligibility

PART 4: Principal Pension Indexes

- 4a. General Index

- 4b. Organizational Index

- 4c. Numerical Index

- PART 5: Alternative Pension Indexes

- PART 6: Case Studies

- PART 7: Getting the Full Pension File

Principal Pension Indexes

Applies to:

- Union soldiers

Although many of the concepts in this series apply equally to southern records, Confederate pensions were issued by the individual southern states. For more information, see our separate post on Confederate Pensions.

There are three principal pension indexes for the Civil War: the General Index, the Organizational Index, and the Numerical Index. The indexes were created at different times, by different government agencies, for different purposes – and they are stored and accessed through different online sources today.

In theory, a specific veteran’s pension will be recorded on a card in each of these systems. In practice, however, a pension record will sometimes be found in one index system but not in one or both of the others. When researching a veteran, it is therefore always advisable (and, as we shall see, sometimes critical) to search more than one index for a veteran’s record.

Even in those fortunate cases where the same record is reflected in multiple indexes, the index cards warrant careful comparison. Since the index cards in each system were handwritten, such a comparison will often resolve issues of interpretation, resolution, and clarity. More importantly, however, each index may include types of data that are not available in the others.

Don’t dismiss references to sites like Ancestry.com and Fold3.com on the grounds that they require a subscription ($). There are several ways to access them for free.

It is therefore very important to understand the different types of indexes, the distinct advantages and disadvantages of each, and where to find them.

NOTE: In the event that you don’t find what you need in the principal indexes, there are alternative indexes that are covered in the next post in this series.{general}

The “General Index to Pension Files, 1861-1934″

The General Index is comprised of pension cards for service in the Union army and navy in the Civil War, as well for service in the Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, peace-time service in the Regular Army, and some civilian service. The General Index is searchable online at FamilySearch.org (free), Ancestry.com (free), and FindMyPast.com ($).

This index contains images of nearly 2.5 million cards that were taken from 546 rolls of microfilm that are housed at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) as Record Group 15 and microfilm publication T288.

Since it is available for free on at least two web sites, this is the first pension index card that is encountered by many researchers.

Pro Tip: FamilySearch.org (free), Ancestry.com (free), and FindMyPast.com ($) will all let you search by the veteran’s name and the state in which he lived at the time of his application.

However, only Ancestry will let you filter the search with the name of his unit, e.g., “39th Ohio Infantry”. That can make a big difference if the soldier had a common name and you don’t know his state of residence. Don’t give up too easily searching by the name of his unit, however, because it might be listed as “39th OH Inf.”, “39 Ohio”, etc. So try different formats of the unit name.

The index contains one card per veteran, although if the card indicates that the soldier had an alias, then there would typically be a second card in that name. The cards are sorted by name, state of service, and then numerical regiment. Each card shows the veteran’s name, of course, and a list of all of the units in which he served.

The card also lists each of the pension applications that were filed with reference to this veteran’s service. For each application it will typically show:

- The Date of Filing: If you correlate the filing date with the laws governing eligibility at that time, you may be able to make reasonable conclusions about the nature of the applicant’s disability or lack thereof. For more information, see Eligibility earlier in this series.

- The Class of Applicant.The first line is for the disabled veteran or “Invalid” himself if he survived long enough to apply.Note that in the General Index, pension cards for service in the Spanish-American War or the Philippine Insurrection are marked with a very small “S” handwritten after the word “Invalid.”

The subsequent lines are for his widow, minor child, or other dependents, e.g., mother, father, orphaned sister. (For further details about the names and codes that describe the type of applicant, see Terminology and Abbreviations earlier in this series). One or all of these lines may be completed in the case of multiple applicants.

- An Application Number: a number assigned by the Pension Office when the application was received, and;

- A Certificate Number: a number assigned if/when the application is approved. The presence of an Application Number without a Certificate Number indicates that the application was rejected or abandoned. (For more details about Application Numbers, Certificate Numbers, and rejected/abandoned applications, see Terminology and Abbreviations earlier in this series).

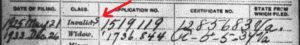

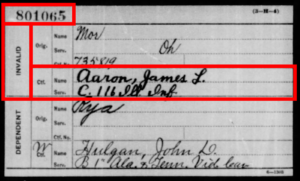

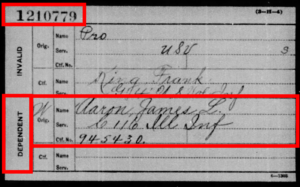

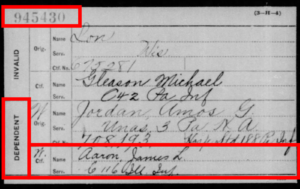

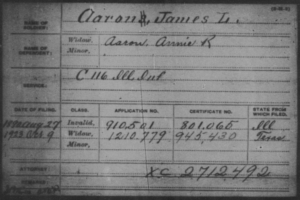

We see in the following example that the soldier, James L. Aaron, applied for a pension on 27 Aug 1890 – two months after the law first allowed a veteran with a non-war-related disability to do so. His widow applied on 9 Oct 1923 – providing a rough estimate of the veteran’s death. Both applications were approved and we have their respective application and certificate numbers, which will be needed in order to obtain the full pension file.

But the General Index also contains three other types of data that are not shown on other types of indexes:

- The “Name of the Dependent”: The name of the spouse, minor child (or guardian), and/or other dependent(s) on whose behalf the application was filed.

- The “State From Which Filed”: This is can be very helpful for further research because it reflects the residence of the applicant at the time of application (often many years after the war) and is not necessarily the same as the state for which the veteran served during the war.

Pro Tip: A search of this index on FamilySearch will produce a list of records that match the name that you entered. That list can be further filtered by “Location” – but that location will be matched against the “State From Which Filed.” It will fail to match the state of the veteran’s service if that happens to be different.

- A C or XC number in the “Remarks” section: This designates a pension that was still active after 1934.

Pro Tip: If a pension has been assigned a C or XC number, then that number is recorded on ONLY the General Index card. It will NOT be reflected in the Organizational Index or Numerical Index that are described later. The presence of a C or XC number will determine the repository in which you will find the full pension file. For this reason, the General Index should always be consulted if you intend to access the full file. For more details about C and XC numbers and their meaning, see Terminology and Abbreviations earlier in this series.

We can draw even more conclusions about James L. Aaron and his pension based on this card. When he applied for a pension in 1890, he was living in Illinois. When his widow, “Annie K.,” applied in October, 1923, she was living in Texas – giving us a good theory about the date and place of his death. The pension file was then assigned #XC2712492, which indicates that she lived until at least 1934. And when we use the “X/XC Number Tester” provided earlier, we see that the pension file itself is most likely housed in the National Archives facility in St. Louis, Missouri.

But the General Index has some disadvantages too:

- This index was originally hand-written on colored paper, which did not always duplicate clearly onto microfilm from which the images were made. The images are therefore often blurry and hard to read. Since this index was microfilmed twice. One is available on FamilySearch.org (free) and the other on Ancestry.com (free), it is often helpful to find both copies of the same card to resolve any legibility problems.

- Some very dark cards were not digitized by Ancestry.com at all. Most of those very dark cards were for Navy pensions.

- It does not include some important types of data that are included only on the Organizational Index (see next).{organizational}

The “Organizational Index to Pension Files of Veterans Who Served Between 1861 and 1900”

The Organizational Index is comprised of pension cards for veterans who served between 1861 and 1900, including the Union army in the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, the Philippine Insurrection, and peace-time service in the Regular Army. It also contains a few records from the Indian Wars and, despite its name, World War I (1917).

This index contains images of nearly 3 million cards that were taken from 765 rolls of microfilm housed at NARA as Record Group 15 and microfilm publication T289.

The Organizational Index is available on Fold3.com ($). It can also be searched on FamilySearch.org (free), but in order to see the actual index cards, you’ll still need to go to Fold3.

This index contains one card for each unit in which the veteran served and is sorted by state, branch, regiment, company, and then name of soldier.

Pro Tip: The Organizational Index is especially good if you know a unit in which a soldier served but you haven’t been able to find his name with the spelling that you expected.

Keep in mind also that many companies were recruited locally so many of the members of the unit knew each other or were even related. Soldiers often provided testimonials for each other in pension applications. And while a soldier’s parent(s) may not be mentioned in his pension file, those parents may be identified (or may even have been applicants) with respect to a different soldier (i.e., a sibling) in the same unit. For this reason, it may prove useful to consult the pension file for every soldier who served in your ancestor’s company – or at least those with the same surname.

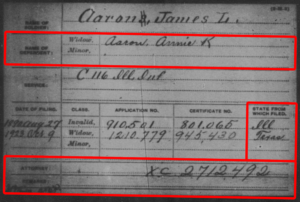

Like the General Index cards, it shows the veteran’s name(s), unit(s) in which he served, and each application that was filed in relation to his service (filing date, class of applicant, application number, and certificate number).

But the Organizational Index also contains some types of data that are not shown on other types of indexes:

- The Rank that he last held in that unit.

- The Terms of Service – or date of his enlistment and discharge in that unit. Since this index should contain one card for his service in each distinct unit, you may be able to track his rank and dates of service over time. (All too often however, these fields are blank.)

- Multiple Dates to show multiple filings by the same applicant. As before, the filing dates can lead you to some reasonable conclusions about this disability or lack thereof.

- His date and place of death.

- Important and enlightening cross-references to other pension index cards. (See Case Study #11).

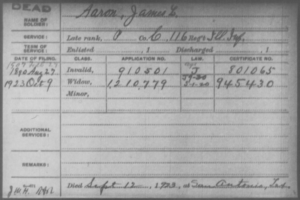

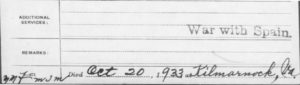

Building on what we already know about James L. Aaron and his pension, we now know that his last rank in the 116th Illinois Inf. was Private. We also see that there was an additional filing date of 27 Feb 1907, which was three weeks after the law was relaxed to allow pensions based solely on age and not requiring any disability. Finally, we know that he died on 12 Sep 1923 in San Antonio, Texas. (Recall that his widow applied on 9 Oct 1923 which we now know was less than a month after his death.)

So we know quite a lot about him, even before seeing the full contents of the pension file.

But there are several disadvantages to the Organizational Index:

- Navy pensions are not included.

- R-number civilian pensions are not included.

- It does not include the name of the veteran’s spouse or dependent(s).

- If the pension was assigned a C or XC number (because the pension was still active as of 1934), then it will not appear on this index. The C/XC number is critical to finding the full pension file but it is shown ONLY on the General Index as described above.{numerical}

The “Numerical Index to Pensions, 1860-1934”

The Numerical Index is typically used as a cross-reference to the two indexes discussed above. It typically contains no unique information about the applicant but can be very helpful in cases where the index card is missing or illegible in the other indexes. The Numerical Index is searchable at Fold3.com ($).

This index is comprised of nearly 6 million pension cards for veterans who served between 1860 and 1934. The images were taken from microfilm housed at NARA as Record Group 15 and microfilm publication A1158. Most of the cards are for veterans of the Union Army and Navy in the Civil War and later wars: the Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, and World War I. But the index includes some soldiers from earlier wars: Indian Wars, Mexican War, War of 1812, and the “Old War.”

This index is comprised of nearly 6 million pension cards for veterans who served between 1860 and 1934. The images were taken from microfilm housed at NARA as Record Group 15 and microfilm publication A1158. Most of the cards are for veterans of the Union Army and Navy in the Civil War and later wars: the Spanish-American War, Philippine Insurrection, and World War I. But the index includes some soldiers from earlier wars: Indian Wars, Mexican War, War of 1812, and the “Old War.”

Pro Tip: To search this index, follow the link to Fold3 ($) where you can navigate to either an Application Number or Certificate Number – or simply type the number in the search field at the top right labelled “People, Records, Places Dates…” and press Enter. You can also type the soldier’s name in that search field in order to see all of the cards that are associated with him.

Even better, you can use wildcards in that field! If you can’t read a number or you are unsure of the spelling of a name, use “?” to represent a single letter/digit or “*” to represent any number of missing letters/digits, e.g., “John Sm?th” or “248*45”.

The structure and contents of the Numerical Index is very unusual and easily confusing. Its format was apparently designed to do several different things at the same time – and to combine them on a single form to save paper. As a result, the Pension Numerical Index often leads to false conclusions. It doesn’t help that there are several variations on this confusing format, as we will show below.

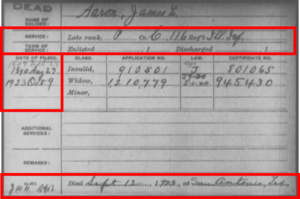

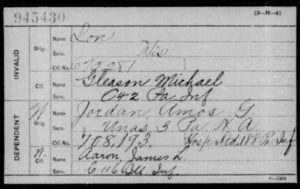

The first thing to recognize about the Numerical Index is that each card references multiple pensions that happen to share the same number but are otherwise unrelated to each other. As we have seen, the Application Number and the Certificate Number are very different things. Similarly, there are independent numbering systems for Civil War veterans and for their dependents. In combination, that’s four completely different numbering systems that are used to track pensions. (And pension numbering systems for veterans of other wars use still more numbering systems).

So a number like 945430 might be the application number for a Civil War veteran’s pension and it might happen to be the certificate number for an unrelated widow’s pension – but there is no connection between those two pensions except that they both happen to use 945430 in different contexts.

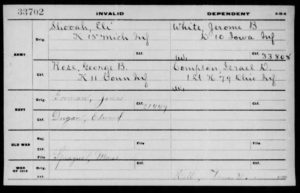

A card in the Numerical Index will therefore have a number in the top-left corner and then it will list all of the pensions that use that number in any context. The card is divided into two sections, Invalid and Dependent, and each of those is divided into two more, “Orig” (Original, i.e., the Application) and “Ctf.” (Certificate). The four sections therefore refer to four different veterans who have no connection to one another other than the fact that their independent numbering systems happen to reference the same number.

In theory, each veteran who received a pension will appear on at least two cards in the Numerical Index: one for his Application Number and one for his Certificate Number.

Here are the cards for our friend from earlier examples, James L. Aaron, of Co. C, 116th Illinois Infantry (Click on any card for a larger view):

Since his widow received a pension, James is listed on two more cards: one each for HER Application and Certificate numbers.

Notice a few things about these cards:

- The name on each card is that of the veteran, even in those cases where the card is referring to the widow’s file numbers.

- A handwritten “W” in the second column indicates that the dependent in this case is the veteran’s widow. Other handwritten abbreviations (e.g., “M” for mother, “C” for child) will be seen there in other cases.

- Some of the names of veterans are abbreviated to the first three characters. This is very common for this index.

Since that’s not confusing enough![]() , there are two other variations of the Numerical Index that the Pension Office used at different times.

, there are two other variations of the Numerical Index that the Pension Office used at different times.

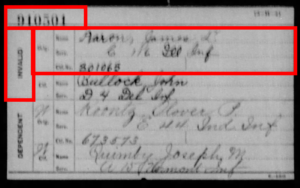

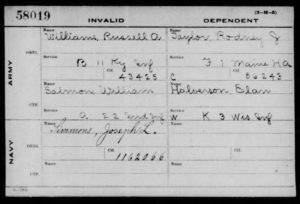

You might encounter this form which crams the pensions of up to EIGHT soldiers onto the same page. The top half (“Army”) is similar to the previous form except that the rows and columns are arranged differently. Be careful to interpret the rows for Application Number (“Orig”) and Certificate Number (“Cft.”), as well as the columns for Invalid and Dependent correctly! The bottom half of this form (“Navy”) leaves room for up to four sailors and their dependents.

Finally, there is this variation of the Numerical Index card:

This form has space for eight Civil War pensions (four army and four navy), two “Old War” pensions, and two War of 1812 pensions.

Please post comments or questions about this post below.

Copyright © 2021, Gopher Records, LLC.